It’s among the most powerful scientific instruments ever built.

The James Webb Space Telescope is scheduled for launch later this month, destined for a point a million miles from Earth where it will unfurl gold-plated mirrors and begin searching the heavens for secrets long kept from humanity.

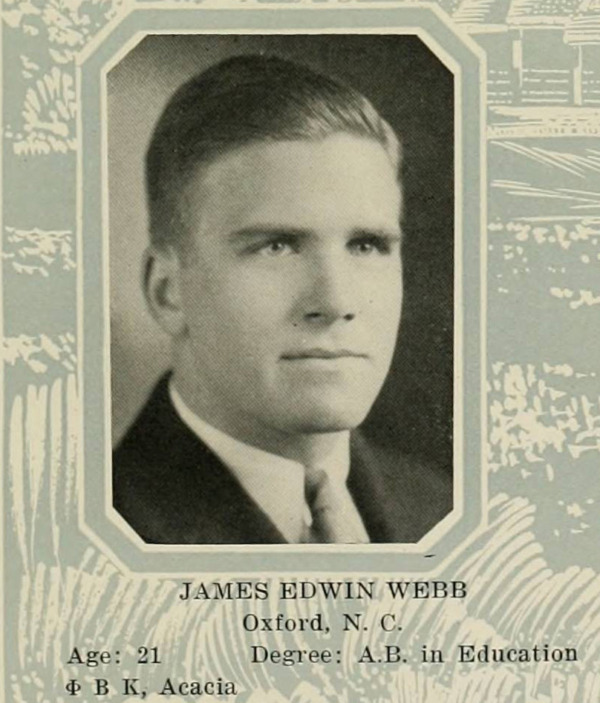

It does so bearing the name of a graduate of the UNC School of Education — James E. Webb (’28 A.B.Ed.).

Photo credit: NASA

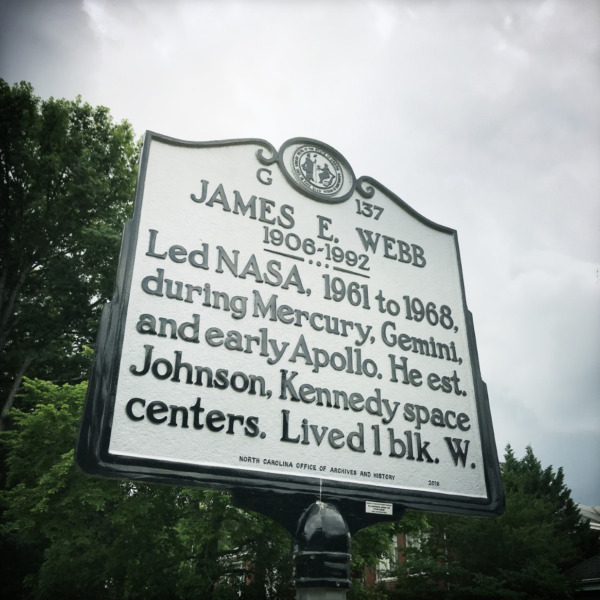

Most widely known as the head of NASA during the Apollo program that put astronauts on the moon, Webb was born in one world and did an outsized part pushing and shoving America into another.

“James Webb was the guy who gave us the wherewithal and the courage to actually explore beyond this rock,” said Sean O’Keefe, who as NASA administrator in 2002, chose to name the telescope after Webb. “He, at a formative phase and a very dramatic phase, with a mission to the moon as his mandate, established NASA for its extraordinary exploration prowess. He was instrumental in that leadership role.”

James Webb was an early proponent of NASA science missions, including those of space-based astronomy. Amid the race-to-the-moon programs of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo, Webb as early as 1965 advocated for putting a telescope in orbit above the fuzzying effects of Earth’s atmosphere, enabling it to see clearly far into space. That idea became the Hubble Space Telescope, an instrument that for 30 years has captured and delivered into laboratories and living rooms stunning star-studded images from space.

If all goes according to plan with its launch and months-long deployment, the James Webb Space Telescope will engage a combination of mirrors, cameras, and computers that makes it 100 times more powerful than Hubble. It will see to just shy of the very edge of the known universe.

Because it will be able to view ancient light from astonishing distances, the Webb Telescope will serve as a cosmic time machine. It will capture baby pictures of infant galaxies as they were being born billions of years ago — before the formation of our home, Earth. By analyzing the light passing through the atmospheres of planets orbiting other stars, the Webb Telescope might discover chemical signatures that for the first time show life has existed somewhere other than here.

James Webb the man helped make it possible.

An early aviator

James Webb was born in 1906, four months after the Wright brothers secured their patent for the world’s first powered airplane. Webb’s career would put him into roles from which he helped push the U.S. to the leadership position of a modernizing — and spacefaring — world.

On the way, through pluck and by luck, Webb worked in business and in government, becoming a fixture in the halls of power in Washington, D.C., holding leadership positions in several offices and agencies, and directly serving three U.S. presidents.

Webb came out of deep rural Granville County, the son of a school superintendent (also a Carolina graduate).

After dropping out of Carolina for a year because he couldn’t afford the costs, Webb learned how to take shorthand and to type, skills he used upon his return to Chapel Hill to work his way through college. He graduated in 1928 with a bachelor’s degree in education and a Phi Beta Kappa key.

He then worked for the School’s dean, Nathaniel Walker, serving for a year as business manager for the Bureau of Educational Research, which created, distributed, and scored tests taken by high school students across the state to determine their readiness for college. North Carolina was one of the first states to give a comprehensive test to all graduating high school students — at the dawn of high-stakes standardized student testing.

He made his way out of Depression-busted North Carolina by applying for and winning in 1930 a slot to join a small, newly formed reserve aviation unit of the U.S. Marine Corps. It was his introduction to flying machines, the people who fly them, and the people who build them.

A budding power broker

The next decade would see Webb in a succession of 20th century jobs that would seemingly singularly prepare him for building and leading what would become a 21st century space agency.

Photo credit: Truman Library

While serving as a reservist in the Marine Corps, flying on weekends out of Quantico, Va., Webb got his first job in government, serving as secretary to North Carolina congressman Edward Pou. Pou was chairman of the House Rules Committee, serving in that gate-keeping role during President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first 100 days in office and the rush to pass reams of New Deal legislation.

Pou made the deals, including at poker games every afternoon at 4 o’clock, and for two years Webb executed them, giving Webb a doctoral-level education in the back-room workings of Washington.

Webb next worked as an assistant to former North Carolina Gov. O. Max Gardner in Gardner’s Washington law firm, while completing his own training to become a lawyer. Webb helped Gardner negotiate a resolution to a scandal involving government air mail contracts, giving Webb experience balancing the interests of government agencies and multiple aviation industry firms.

As the nation prepped for war in the late 1930s, one of those aviation industry firms, the Sperry Gyroscope Company, hired Webb, who, over eight years, rose to vice president of the company while managing its growth from 800 employees to more than 33,000 as the firm produced gyroscopes, navigational equipment, bomb sights, and other gear for fighting World War II. Late in the war, Webb asked to join active duty in the Marine Corps and was assigned to lead a unit at Cherry Point, N.C., that produced portable radar equipment bound for use in the island-hopping warfare of the Pacific theater. The jobs gave Webb experience growing and managing large technical teams that had hard-set, life-and-death objectives.

After the war, Webb was called back to Washington to serve President Harry Truman as director of the Bureau of the Budget, the predecessor of today’s Office of Management and Budget. One of Webb’s initiatives aimed at better understanding the country’s needs and capabilities in a modernizing world: He instructed all government departments and agencies to report to him the amounts of money they were spending on research and development work. The resulting report was used to help make the case for creating a body that would help prioritize and guide government investments in scientific research — the National Science Foundation.

Truman promoted Webb to the No. 2 position at the State Department, a position in which he served during the outbreak of the Korean War and as the U.S. government organized itself for the emerging Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Webb’s tenure at the State Department has generated criticism today from people pointing to the government’s purging of gay and lesbian employees, including during Webb’s time at the State Department and in later years at NASA, during a McCarthy-era persecution campaign that has been called “the Lavender Scare.” A petition drive led by a group of astronomers called for the Webb Telescope to be renamed, saying Webb either was involved in the purges or should have known enough to stop them. A NASA investigation into available documents concluded in September that there was not enough evidence of Webb’s involvement to justify renaming the telescope.

A scientist of management

After the Soviet Union launched the first man-made satellite — “Sputnik” — in 1957, the U.S. raced to catch up and to find a way to demonstrate that a democracy could compete, and surpass, the Soviets’ achievements in space.

Photo credit: Abbie Rowe. Courtesy of John F. Kennedy Presidential Library

Webb was put in charge.

He was named NASA administrator in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy, who told Webb he needed not a scientist to lead the space agency, but someone who knew how to get things done in Washington. Fourteen weeks later, in a speech to Congress, Kennedy called for landing men on the moon by the end of the decade.

Webb is widely credited with how he managed NASA’s efforts and its bold goals. A student of management theories and a proponent of professionalizing government management (he established the National Academy of Public Administration in 1967), Webb organized and managed the race to the moon. In dollars spent, it would become the largest engineering project in history, as much as ten times larger than the Manhattan Project that built the first atomic bomb. In numbers of personnel, it rivaled the American involvement in the Vietnam War.

Webb was admired within NASA for his leadership through crisis after the 1967 Apollo 1 launchpad fire that killed astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee. Webb shouldered responsibility — in repeated grilling by congressional committees — and promised a full investigation, one that uncovered and fixed technical and management problems that contributed to the accident.

Sean O’Keefe, who was NASA administrator in 2003 when the Space Shuttle Columbia broke up on re-entry, killing all seven onboard, said he was guided by how Webb handled the Apollo 1 disaster.

“Had I not been as familiar with that history with him and his role in it, I don’t know that I would have handled the Columbia tragedy the way I did,” O’Keefe said. “I thought, ‘I’m going to take a page right out of that book and follow that directly.’”

An evangelist for science

Throughout the construction of the Apollo moon program, Webb often worked to stay out of the news, putting forward astronauts, scientists, and other administrators to be in front of the cameras. In a pre-Internet age when many Americans got their news from newspapers and weekly news magazines such as “Life,” Webb never appeared on a magazine cover during the race to the moon.

From outside the stage lights, he worked to build a national infrastructure to support the development of scientists and engineers across a range of disciplines. He pushed, and funded, universities to pursue multidisciplinary approaches to large research problems. He was an evangelist for university-corporate-government research partnerships. Both are norms today.

Photo credit: Michael Hobbs

As a graduate of a public university in the South, he knew that with support, colleges and universities outside of the Ivy League could make major contributions to the nation’s scientific and technological progress. Through his administration of NASA, he targeted millions of dollars of funding for science programs at universities throughout the country, including historically Black ones, with grants to support graduate students. At his effort’s height, NASA was the nation’s largest funder of graduate student aid, with more than 4,000 doctoral graduates benefiting from the funding.

While not a scientist himself, Webb traveled the country, frequently articulating a vision in which science, particularly the discoveries emerging from the space program, would build American national prestige. It would also, he said, excite young people, motivating many of them to pursue careers in mathematics, engineering, and science.

James Webb would leave NASA in late 1968, resigning to make way for the next president to choose his own administrator. A few months later, Webb would watch Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong step onto the moon as most Americans did — on television at home.

‘A search for truth’

Webb went on to serve on a variety of advisory and corporate boards and for 12 years as a member of the governing board of the Smithsonian Institution. He died in 1992 at the age of 85 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Fouad Abd-El-Khalick, dean of the UNC School of Education, said Webb’s life not only bridged a period in which the U.S. boldly moved into leadership of a technocratic age, but that Webb helped make it so, by demonstrating the power of organizing varied disciplines to confront a shared, challenging problem.

“In many ways, James Webb was a man of his time, but also one who could see not only possibilities of grand achievements, but also ways to get there, ways to manage and motivate people to reach for incredible goals,” Abd-El-Khalick said. “His accomplishments helped popularize the aspirations of science, and for that we are indebted to him.”

In a ribbon-cutting speech in 1964, Webb talked about the need for the public to understand that the work of science is not separated “by some mystique from our humanitarian traditions.”

It is important for people, he said, to “understand that the world of science is a world of accumulated knowledge, not a world of magic or mystery. They will see how slowly, painstakingly the scientists unveil knowledge that has not been disclosed by the inquiries of the past; that science is a search for truth, and that so are philosophy and history and poetry.”

The Webb Space Telescope is bound for flying beyond the moon, to a station-keeping point where it will unfold its mirrors, point into the distance, and begin six months of calibrating its cameras and instruments. NASA and its scientific partners already have plans for which objects will be targeted for the first public photos to be released in the second half of 2022 — but for now, that’s a secret.

Learn more about the James Webb Space Telescope:

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s website about the telescope.

NASA’s “Curious Universe” podcast is airing a series about JWST.

The Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago hosted astronomer Heidi Hammel for an online discussion titled “Will the James Webb Space Telescope See God?” Hammel, who has won awards for her work explaining science to the public, gives an overview of JWST and the science it will pursue.