The following article is from the Fall 2021 issue of Edge: Carolina Education Review.

Every child is entitled to a sound education.

But children have different needs and different abilities, living with varying levels of environmental supports.

How can educators, counselors, clinicians, policymakers, and others ensure equitable educational opportunities for all children while accounting for the wide variation of each child’s or youth’s needs, especially those with disabilities?

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health-Children and Youth Version is designed to answer that question.

The system — also known by its acronym, ICF-CY — was established by a group of clinicians, health advocates, special education researchers, and others, with Rune J. Simeonsson, a professor at the UNC-Chapel Hill School of Education, frequently in the forefront of the work. The ICF-CY was adopted in 2007 by the World Health Organization, which promotes its use across the globe.

The ICF-CY is designed to provide more information about an individual’s abilities than is conveyed simply by a clinical diagnosis. Beyond assisting in the development of individually tailored interventions, use of the ICF-CY also provides standardized data that can be used by researchers across various cultural settings, including on a global scale.

Decades of commitment to needs of children

Simeonsson has conducted research in developmental disabilities for more than 50 years, with a focus on the study and development of systems that improve the description and classification of children’s functioning so that more appropriate interventions can be developed and implemented for each child.

Simeonsson, a professor of school psychology and early childhood education who holds an appointment as a fellow at UNC’s Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, has devoted his career to teaching and research in child development, special education and public health, particularly the developmental and psychological characteristics of children and youth with chronic conditions and disabilities.

He is the author or a co-author of seven books and more than 200 journal articles. He has made more than 250 national and international presentations across six continents and 45 different countries, with more than half of these presentations being invited papers. Simeonsson’s work has attracted more than $20 million in federal funding from the National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Department of Education.

In 2011, he was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Disability Section of the American Public Health Association.

A disability diagnosis does not predict child functioning, nor inform specific areas to target for interventions. A diagnosis also rarely includes environmental factors as part of its criteria. The ICF-CY fills these gaps.

Example 1: A child in a teacher’s classroom may have been diagnosed by a pediatrician with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. However, the diagnosis provides the teacher little information about the child’s specific abilities. Additionally, a classroom may have more than one student diagnosed as having ADHD, each having problems of varying levels of severity.

For a child with ADHD, impairments might include difficulty with attention or poor control of impulses. Activity limitations might include difficulty focusing attention and carrying out multiple tasks. Restrictions in participation could include being excluded in the past from social activities and receiving poor grades. Environmental factors, such as level of access to health care, underly the other elements.

The ICF-CY offers codes, accompanied by severity indicators, for each of these sorts of factors (Lollar, 2005).

Example 2: Autism spectrum disorder includes many manifestations, with wide variability across cognitive and intellectual levels, as well as social, emotional, communication, and behavioral factors. Assessments using the ICF-CY capture each child’s unique levels of ability, or the severity of their limitations, and other factors, allowing clinicians and educators to design individualized interventions.

Roots of the ICF-CY System

Simeonsson chaired the World Health Organization committee that developed the ICF-CY classification system.

Development of the ICF-CY follows a long line of work to classify and better understand human illness and disability.

Efforts to create classifications for causes of death and types of disease began in the mid-1800s. Since then, the International Classification of Diseases, or ICD, has matured into a system that provides, among other things, diagnostic codes for diseases and conditions, allowing for international comparisons in health and wellness statistics. The ICD, which is maintained and published by the WHO, has become part of a family of international classification systems used in health and helping professions.

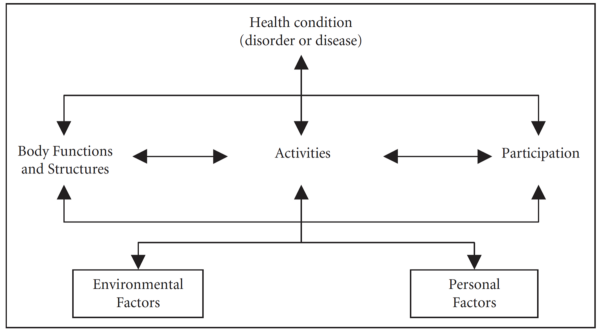

Another classification system within that family is the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, known as the ICF. The ICF, adopted by the WHO in 2001, is designed to complement other classification systems by going beyond diagnoses and providing detailed descriptions of individuals’ actual functioning, activities, and environmental factors that affect the individual.

Simeonsson and other researchers recognized, researched, advocated for, and designed a variation of the ICF that could account for children and youths’ rapid and changing development and aspects of their living and schooling environments that differ from those of adults. The result was the ICF-CY system.

Going beyond diagnoses

While governments typically establish distinct agencies, departments, and programs to manage different aspects of education and health and human services, there is a growing appreciation that separation of these fields can inhibit interventions that serve individuals and groups. A holistic classification system such as the ICF-CY can bridge discipline-specific languages to promote integrated views of the needs of children and youth (Simeonsson, 2017).

Additionally, a disability diagnosis does not predict child functioning, nor inform specific areas to target for interventions (Simeonsson, 2006). Although diagnoses are important for defining cause of an illness or impairment and for projecting a prognosis, identifying limitations of function is often the pivotal information needed for planning and implementing individualized interventions (Lollar, 2005).

What is needed, Simeonsson and others advocate, is a system that captures and describes the complexity of child and youth functioning within their environment across various dimensions, including physical, mental, emotional, and social ones.

“What are the demands of the environment and how do we match them with a child’s skills?” asks Simeonsson. “That’s what any good teacher does.”

The ICF-CY is designed to provide a profile of an individual’s characteristics, giving information beyond diagnoses, using neutral, nonjudgmental terms to describe children’s and youths’ abilities and limits, rather than relying upon terms that describe deficits, with special utility for developing interventions for children and youth with special education needs. A key component of the system is that it describes the severity of any of a child’s disabilities.

Contributions of the ICF-CY for serving individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities:

• A unifying framework for interdisciplinary work

• A classification of dimensions and health

• Profiles of functional characteristics and morbidity

• Functional indicators for framing intervention and outcomes

• Identification of environmental barriers and facilitators

• Continuity of documentation in transitions across services and time

• Common language for data management and health informatics

• Standard reference for defining rights of children and adults with disabilities

(Simeonsson, 2009)

The ICF-CY documentation of functional profiles also can be used to identify school-wide and individual special education needs, determine resource allocation, develop educational goals, and demonstrate intervention outcomes (Ellingsen, 2018).

Because it provides a common language describing individuals’ abilities and disabilities, the ICF-CY is applicable and useful globally, including across all socio-cultural contexts, facilitating comparisons by researchers and policymakers.

The ICF-CY provides families, educators, clinicians, and others a holistic approach to individual children’s special education needs, considering each child from the point of view of the activities in which they engage, their participation, the environments in which they grow up, in addition to body functions and structures.

Rather than relying simply on the label of a clinical diagnosis, the ICF-CY’s approach is that any disability has many factors, with impairment that can occur at many levels. Likewise, development or improvement occurs — often at different rates — at biological, psychological, environmental, and social levels.

The ICF-CY uses a comprehensive list of codes that define different aspects of functioning and environmental factors. A questionnaire — which can be filled out by a parent, educator, psychologist, counselor, or as a self-reporting tool when age-appropriate — is used to identify codes that are used to create individualized profiles that serve as the basis for intervention planning and assessment of the efficacy of interventions.

The ICF-CY manual provides a list of 1,685 categories, providing a common language and terminology for recording problems manifested from infancy through adolescence (Riva, 2010).

The ICF-CY’s system of codes lies within two overall components.

The first component describes the child’s or youth’s body function and structures, capturing details about the individual’s anatomy and physiology. It also describes such items as the child’s activity and participation, capturing details about her or his communication, mobility, self-care, and interpersonal interactions.

The second overall component includes factors that affect the child; environmental factors — such as family setting, home supports, societal services, and policies.

The ICF-CY uses an alphanumeric coding system. The letters “b” for Body Function, “s” for Body Structures, “d” for Activities/Participation, and “e” for Environmental Factors. The letter is followed by a numeric code that starts with one digit identifying the domain being described (referred to as “chapter” within the ICF-CY). The following four digits represent categories and subdivisions nested within that domain.

The qualifier code follows a decimal point, with values from 0 meaning “no problem” to 4 indicating “a complete problem.”

For an example, the code b1440.2 identifies moderate difficulty with short-term memory, with the following components of the code:

• b=Body Function

• b1=Mental Functions

• b144=Memory Functions

• b1440=Short Term Memory

• b1440.2=Short Term Memory, moderate difficulty

Extending understanding of the ICF-CY

Development of the ICF-CY is part of a global initiative to promote early child development, with roots in the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which declared “A mentally or physically disabled child should enjoy a full and decent life in conditions which ensure dignity, promotes self reliance and facilitates the child’s active participation in the community.”

Simeonsson co-led — with Matilde Leonardi, a neurologist from the Italian National Neurological Institute — an international work group established by the WHO in 2001 to establish the ICF-CY. The first draft in 2003 was field tested in the United States, Europe, and countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Additional input from providers, practitioners, researchers, and policymakers went into development of the final version of the classification system.

While the ICF-CY has not yet been widely adopted within the United States, it is being used in other countries and is studied around the globe. Portugal was the first country to mandate use of the ICF-CY in national special education policymaking. Taiwan has adopted legislation to incorporate use of the ICF-CY, and Switzerland uses the system to determine special education services eligibility. The system is also being tested in Italy, Brazil, Sweden, Armenia, Australia, and Thailand (Ellingsen, 2017).

Simeonsson and other researchers continue to study implementation of the ICF-CY, with a growing body of literature on the validity of the system; its utility in planning interventions, including the feasibility of using the system within schools; and of the need for more widespread training to facilitate more widespread adoption of the system.

Researchers have documented that the ICF-CY offers a standard way to describe characteristics of children and youth with disabilities, and to supply qualitative and quantitative data that can be used to assess needs and to evaluate interventions at individual, group, and state, national, or even global levels.

They have documented that the ICF classification system has been implemented in three ways around the world: 1) As a tool to support the work of professionals who work with children with disabilities and special needs, 2) as a theoretical model that helps to rethink disability and special needs, and 3) as a model that can be applied to support policy decision-making about the provision of services for those with disabilities and special needs (Castro, 2017).

Researchers advocate that the ICF-CY can serve as a standard reference for documenting the rights of children, for assessing efforts to meet their needs and to support efforts to reach globally adopted sustainable development goals.

As Schiariti and Simeonsson (2021) put it: “For children to realize their developmental potential, there is a priority to ensure equitable access to appropriate screening, assessment, and intervention. …

“Continued work is needed globally to support children’s developmental trajectories toward positive outcomes. This is especially true as countries adapt assessment and intervention practices in the face of evolving environmental impacts of poverty, natural disasters, pandemics, societal and economic changes to prevent the loss of developmental potential of all children.”

References

Castro, S., & Palikara, O. (2017). A classification for functioning: The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. In Susan Castro, Olympia Palikara, An Emerging Approach for Education and Care: Implementing a Worldwide Classification of Functioning and Disability. Pp. 1-2. Routledge: London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315519692

Ellingsen, K., Karacul, E., Chen, M.-T., & Simeonsson, R. J. (2017). The ICF goes to school: Contributions to policy and practice in education. In Susan Castro, Olympia Palikara, An Emerging Approach for Education and Care: Implementing a Worldwide Classification of Functioning and Disability. Pp. 115-133. Routledge: London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315519692

Lollar, D. J., Simeonsson, R. J., & Nanda, U. (2000). Measures of outcomes for children and youth. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 81(12 Suppl 2), S46–S52. https://doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2000.20624

Lollar, D. J., & Simeonsson, R. J. (2005). Diagnosis to function: Classification for children and youths. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 26(4), 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200508000-00012

Riva, S. & Antonietti, A. (2010). The application of the ICF CY model in specific learning difficulties: A case study. Psychology of Language and Communication, 14(2) 37-58. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10057-010-0009-2

Schiariti, V., Simeonsson, R. J., & Hall, K. (2021). Promoting developmental potential in early childhood: A global framework for health and education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 2007. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042007

Simeonsson, R. J., Leonardi, M., Lollar, D., Bjorck-Akesson, E., Hollenweger, J., & Martinuzzi, A. (2003) Applying the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to measure childhood disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25:11-12, 602-610, DOI: 10.1080/0963828031000137117

Simeonsson, R. J., Scarborough, A. A., & Hebbeler, K. M. (2006). ICF and ICD codes provide a standard language of disability in young children. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 59(4), 365–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.09.009

Simeonsson, R. J. (2009). ICF-CY: A universal tool for documentation of disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 6(2), 70-72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2009.00215.x

Simeonsson, R. J., & Lee, A. (2017). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health-Children and Youth: A universal resource for education and care of children. In Susan Castro, Olympia Palikara, An Emerging Approach for Education and Care: Implementing a Worldwide Classification of Functioning and Disability. Pp. 5-22. Routledge: London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315519692

World Health Organization (WHO). (2007). International classification of functioning, disability, and health: Children and youth version. Geneva. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43737/9789241547321_eng.pdf?sequence=1