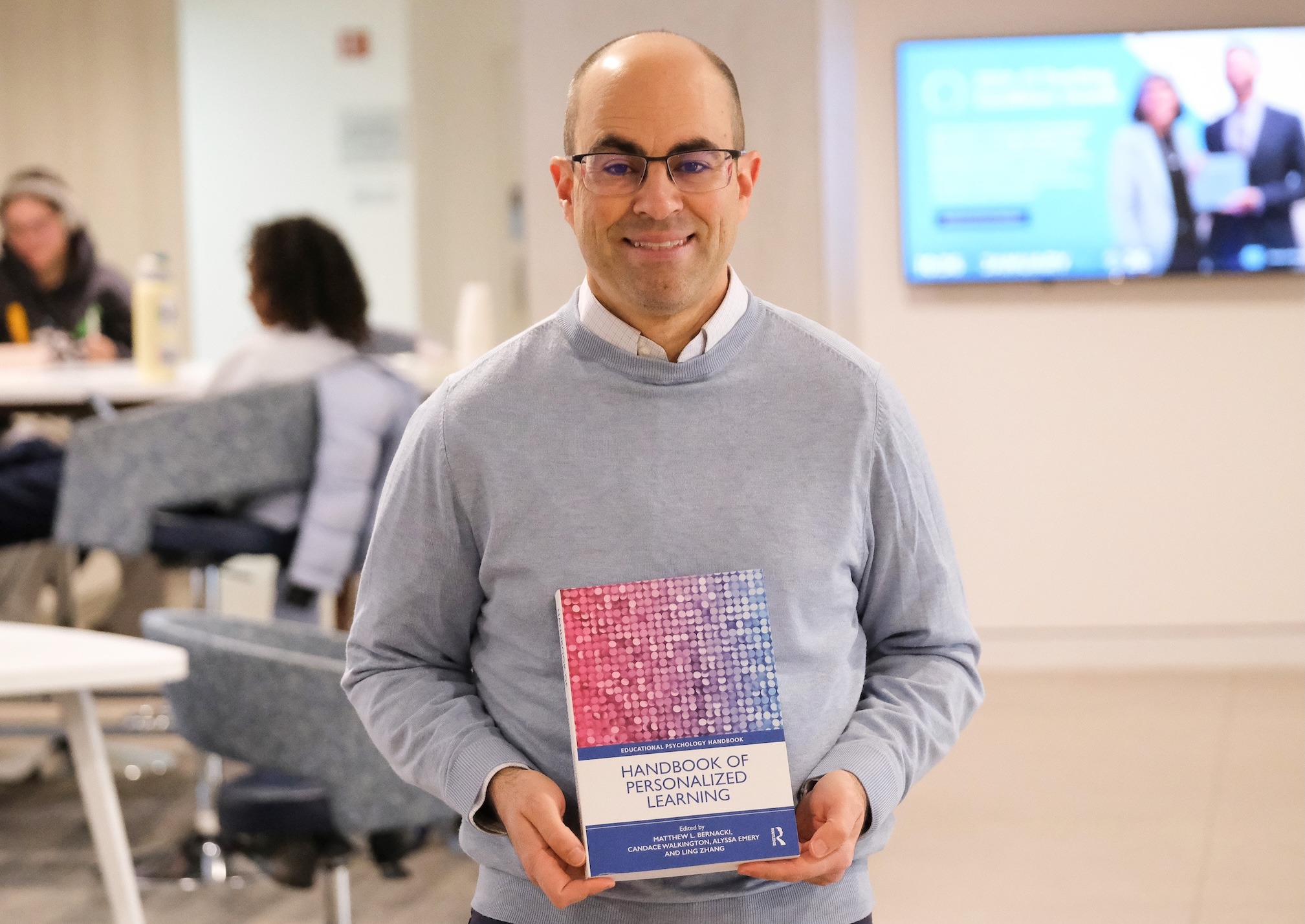

In a new handbook, Matthew L. Bernacki, Ph.D., a leading scholar in learning sciences and learning analytics and the Kinnard “Kin” White Faculty Scholar of Education at the UNC School of Education, and his co-editors brought together decades of interdisciplinary research to examine how learning can be more effectively personalized across educational settings.

Released online in November 2025 by Routledge, “The Handbook of Personalized Learning” offers a comprehensive, theoretically grounded approach for teachers and educators to design and implement personalized learning. The volume draws from educational psychology, learning sciences, cognitive science, and educational technology to explore how instruction can be adapted to learners’ prior knowledge, interests, motivations, and identities.

Bernacki’s co-editors include:

- Candace Walkington, Ph.D., professor of mathematics education and the Annette and Harold Simmons Centennial Chair in the Department of Teaching and Learning at Southern Methodist University

- Alyssa Emery, Ph.D., assistant professor of learning sciences in the School of Education at Iowa State University

- Ling Zhang, Ph.D., assistant professor of special education in the College of Education at the University of Wyoming

Across 26 chapters, contributors present research-informed models and practical exemplars that help teachers, instructional designers, and educators in other learning contexts move beyond one-size-fits-all instruction and toward learning environments that respond meaningfully to individual learners.

Bernacki, who also serves as program coordinator for the School’s Learning Sciences and Psychological Studies Ph.D. concentration, is a leading scholar whose research focuses on self-regulated learning, motivation, metacognition, and learning analytics. In his work, he examines how learning technologies and data-informed designs – including personalized learning platforms for math and STEM learning – can support student engagement and achievement while advancing more accessible and effective educational practices. Bernacki also co-leads the School’s Center for Learning Analytics, a collaborative team of learning scientists, data scientists, and education researchers working to develop practical, research-informed solutions that leverage emerging technologies to address challenges faced by educators and researchers.

In the following Q&A, Bernacki discusses the origins of “The Handbook of Personalized Learning,” the guiding framework that shaped the volume, and how educators and researchers can apply its insights to design learning experiences that center students’ strengths and promote deeper learning.

What inspired you and your co–editors to develop “The Handbook of Personalized Learning”?

Google search results! It’s a common practice to try to cite a handbook for a field when proposing new research, but when I searched for one, all I found was a quickly assembled how-to guide for district leaders who were hard-pressed to align policies and programs with the personalized learning language introduced in the Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015. Drafting this new handbook felt like a real opportunity to introduce educators to a rich history, grounding theories, time-tested exemplars, and an instructional design formula that, combined, help instructors – teaching at any level – build on students’ strengths by personalizing learning opportunities and leveraging each student’s strengths to make instruction more effective.

Personalized learning has roots across several disciplines. How does this handbook bring together perspectives from educational psychology, cognitive science, and learning sciences to form a unified framework?

In addition to overlapping with instructional practices in special education, personalized learning shares language and origins with instructional design theories, including models of adaptive learning and mastery learning. While these approaches emerged from educational psychology, educational technology, and cognitive psychology communities, they share a common underlying assumption: effective instruction should center on the learner, keep track of what learners know, feel, or think in the moment, and draw on instructional theory to adjust learning opportunities to help each learner progress toward their goals.

The handbook features 26 chapters from a wide range of scholars. What guiding model helped you and fellow co-editors curate such a varied yet cohesive collection?

The guiding model actually shows up in chapter 3, and is a single diagram meant to serve as a template for all chapter authors to illustrate their personalization example. That diagram doubles as a guide for all readers to use as a resource to brainstorm and develop their own personalized learning logic that they can enact for their learners.

In simplest terms, the “extensible model of personalized learning” prompts a teacher or designer to name a learning goal they have for their students and to consider the theory and evidence about what promotes that learning goal. They can name these pieces – the objective that motivates the instruction and the assessment of whether they’ve mastered the objective as a result of instruction – to their classic instructional design.

Then they can focus in on their instructional opportunity: teachers and designers can consider their curriculum and materials to identify activities already in place that are designed to enable learners achieve the learning goal, whether they meet the needs of all students, and whether some students might be particularly able to thrive in that learning activity, if the activity can tap into something about their knowledge, motivations, beliefs, or other assets they bring to the learning task. By that I mean, a student might be able to leverage their interests and knowledge from outside of school settings, a future goal or outcome they desire, the satisfaction they get from having opportunities to make choices during learning, or other things that – when unlocked – would allow them to really thrive in the learning activity.

Once those assets are declared, the educator can establish the “theory of change.” In that diagram, the educator documents where they could go to “notice” that asset by identifying a place where data about each learner is stored. These can include gradebooks, learning journals, surveys, or even in the moment polls or choice points educators build into activities. The theory diagram documents how the presence of an asset will be tapped and used to drive the design logic, which adapts something about instruction when a student-specific data point is present. This drives the personalized learning design, and that design should work better than a non-personalized version to help the student achieve their goals more efficiently. Individual chapters demonstrate these theories of change in worked examples, and center on learner characteristics, instructional designs, academic subjects, and learning environments.

How does this handbook reconcile the language and methods educators encounter as they are asked to individualize and differentiate instruction, or respond to demands for customized educational experiences?

This weighed heavily on the mind of our co-editor Ling Zhang. When we proposed the handbook, Ling was a postdoctoral researcher here in the School of Education at Carolina who brought experience in special education and a desire to explore how personalized learning could be used as a method to serve every student — with and without a special education designation — in a more integrated classroom environment. Ling led two chapters of the handbook. In one, she and colleagues examine the intersection of individualized instruction common in special education, the differentiation teachers strive to deliver in classrooms, and the principles of personalized learning. In the other chapter, she and a colleague focus on building a shared language drawn from across these traditions so that educators can talk with one another rather than pass one another.

Many chapters highlight the role of technology in personalizing learning. What aspects of technology are essential to personalization?

Teachers have been adapting their methods to meet student needs since the beginning, so the idea of personalized learning is far from new. Teachers can adapt in classrooms without technology using methods like testing the whole class’s knowledge or polling about common interests and adjusting coverage and the themes of examples to meet them where they are in terms of their knowledge or interests. Differentiation in classrooms can further meet the needs of groups with common knowledge or interest. But at some point, a system that maintains a record of each students’ knowledge, progress, interests, and tendencies can help teachers monitor and support all students more effectively.

Technology becomes essential when education hits a certain scale, and many technologies, like intelligent tutoring systems, have decades of evidence that show how adapting learning opportunities to match students’ level of knowledge or framing them in the context of students’ individual interests have positive and powerful effects on learning and achievement.

How are more recent educational technology innovations reshaping personalized learning today?

When we proposed the handbook, artificial intelligence referred to the cognitive models and adaptive systems introduced in our exemplar chapters, approaches we describe as well-studied, effective designs for personalization. Generative artificial intelligence tools, such as large language models (LLMs), emerged while contributors were authoring their chapters, which posed a challenge.

However, in the “future directions” sections of several chapters, readers will see how researchers are already finding thoughtful ways to incorporate LLMs into personalized learning opportunities.

One of the strongest examples comes from co-editor Candace Walkington, who led the chapter on personalizing learning opportunities around students’ interests. For more than a decade, we have surveyed students’ interests and incorporated them into math word problems, but this process is time-consuming and, while effective at covering common interests, does not always capture highly specific individual interests, or keep up with the pace that they change. Integrating LLMs into the generation of educational materials can incorporate students’ interests on the fly, and with some safeguards, this can promote just-in-time personalized learning opportunities.

Looking ahead, what do you hope researchers and educators will take away from this volume as they design personalized learning tools and experiences?

My greatest hope is that we’ve provided educators with a sufficient recipe and a sufficiently stocked pantry of ingredients that they can bring together their own knowledge of their students, their expertise in an academic subject and instruction, and their personal creativity to develop personalized learning opportunities for students. I’m excited to begin meeting with teachers and set up workshops where we figure out how to support handbook readers who wish to make use of the handbook’s design template and chapters to inform their own personalized learning designs.