Researchers have long endeavored to develop educational interventions that improve student outcomes, only to see them fail when they are scaled to wider use. Today, scholars are working to better understand why some innovations are implemented and other are not. Lora Cohen-Vogel is one such scholar.

She is one of a small but growing number of researchers charting a course for a new science of improvement in education. They have attracted the attention of foundations and the federal government who have begun to fund studies to better understand the conditions under which implementation of educational interventions are successful.

The work received a substantial boost when the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, under the leadership of Anthony Bryk, urged researchers and educators to come together to answer, “what is the problem we’re trying to solve, what is the change we’re putting in place, and how will we know if that change is an improvement?” (Bryk, 2010). Researchers have responded, seeking to uncover how improvement methods can be used in education.

In education, researchers have begun to use improvement science to uncover not only ‘what works’ in education but also to understand ‘what works where, when and for whom.’ Lora Cohen-Vogel is among a handful of scholars helping to bring the approach into education. In her words, “the science of improvement emphasizes innovation prototyping, rapid-cycle testing, and spread to generate learning about what changes, in which contexts, produce improvements.” In leading a team of researchers through the National Center on Scaling Up Effective Schools, Cohen-Vogel has not only recognized the promise of improvement approaches for schools and school systems but also identified challenges involved in the work. Understanding these challenges – challenges she recasts as “dilemmas” – will, she argues, inform future efforts to employ improvement science methods in schools and other educational settings.

Applying improvement science in education

Improvement science has its roots in industry. It is generally attributed to statistician W. Edwards Deming who developed a framework for continually improving work and production in manufacturing.

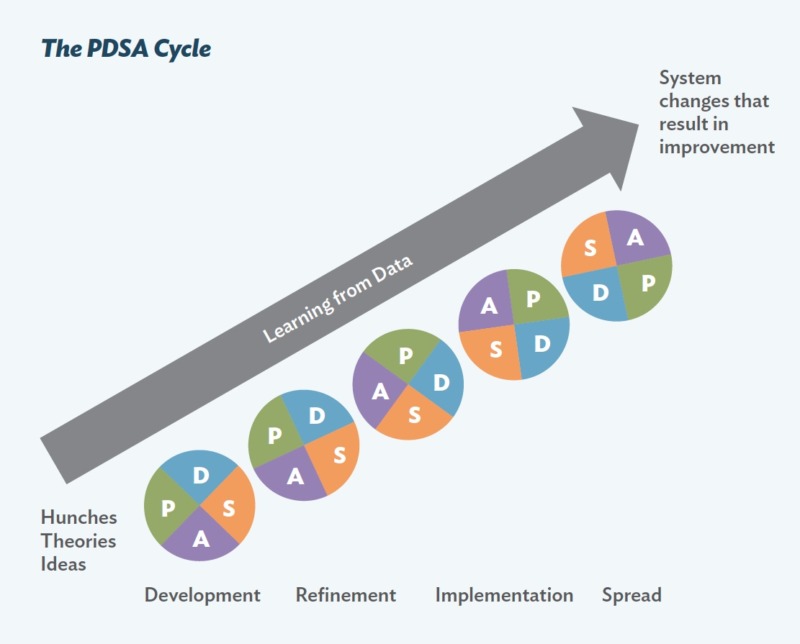

Theoretically and in practice, the framework works to achieve improvement throughout a system – whether it be healthcare, criminal justice, or education – through the use of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles. These cycles guide educators, clinicians, and other practitioners to set measurable aims and test whether the changes they make result in improvement.

Specifically, during PDSA cycles, improvement teams PLAN the test, asking what change will be tested and with whom, and what is expected as the result of trying out the change. Next, the team DOES the test, gathering information on what happened during the test and as a result of it. The team STUDIES the information gathered during the test, comparing it with their expectations. Having studied the information, the team ACTS, making a decision about whether to abandon the change, revise it, or scale it up with a larger number of users.

After testing the change on a small scale, PDSA cycles repeat. The improvement teams learn from each test, refine the change, and then implement the change on a broader scale—for example, in education, with an entire grade level. After successful implementation within a unit, the team can continue to use PDSA to spread, or bring to scale, the change to other parts of the organization or other organizations entirely.

Deming demonstrated the effectiveness of PDSA techniques in post-war Japan, helping spark the rebuilding of that nation’s industry. During the past two decades, improvement science has migrated from industry to healthcare and, from there, into education.

Researchers’ efforts to introduce improvement science in education has shown early promise. An example is the Middle School Mathematics and the Institutional Setting of Teaching (MIST) project, in which researchers worked in partnership with practitioners in four school districts to improve mathematics instruction at scale (Cobb et al. 2013). The work led to new decision-making routines and robust instructional improvements among teachers.

Because the application of improvement science is new to education, relatively little work has been done to uncover the viability of its widespread use in K-12 public school settings. A $13.6 million, five-year IES-funded initiative – the National Center for Scaling Up Effective Schools – was established to begin helping to provide that evidence by developing understandings around how to deploy improvement approaches and the challenges associated with those efforts.

Lora Cohen-Vogel, UNC-Chapel Hill’s Frank A. Daniels Professor of Public Policy and Education, has served as associate director and co-principal investigator with the Scale Up Center, helping lead a team to produce practice-based improvement tools that educators can use in partnership with researchers as they work to bring effective instructional strategies to scale. The team has also published dozens of articles to help understand the promise and pitfalls of improvement science in education and aimed at informing further efforts to use it.

Aiming for change beyond any one innovation

Working with high schools in two of the nation’s largest school districts – Broward County, Florida, and Fort Worth, Texas – the Scale Up Center developed and tested a process in which researchers worked with educators to identify practices that had been shown to improve student achievement in their district, then worked to scale those practices into other classrooms and schools. The process relied on three core principles:

- First, a researcher-practitioner partnership is developed to engage people with diverse expertise as equals in the work, leading to a sense of collective ownership and accountability;

- Second, a prototype is built to reflect the core elements of programs or practices that have been shown to be effective locally;

- Third, PDSA cycles are used to test the prototype and adapt it to new contexts in which it is tried (Cohen-Vogel, et al. 2015).

The first core principle – the development of a research-practice partnership – disrupts traditional roles, taking advantage of the partnerships’ knowledge and expertise and boosting the rate at which change can occur. They challenge the assumption that researchers produce high-quality research, make it clear and accessible, and then practitioners should apply it to their work in the classroom. According to Vivian Tseng of the W.T. Grant Foundation, “without a concomitant focus on how practice should inform research, we risk privileging researchers’ perspectives and relegating practice professionals to the receiving end of research and dissemination efforts.”

Second, a prototype is designed that reflects the programs and practices that have shown promise locally. The Scale Up Center researchers spent three full weeks at each of four district high schools. They interviewed principals, guidance counselors, teachers and department heads and conducted focus groups with teachers and students. They conducted over 700 classroom observations and shadowed students. Researchers found that the higher performing high schools in the district had strong and deliberate organizational structures, programs, and practices that attended to both students’ academic and social learning needs. The organizational structures supported meaningful conversation and interactions among adults and students from ninth grade through graduation. These structures included targeted looping, comprehensive and consistently enforced behavior management systems, and coherent data driven practices. Researchers and practitioners used these findings to build a prototype that came to be known as PASL, or Personalization for Academic and Social Emotional Learning.

Third, PDSA cycles are used to test the prototype, refine it using the data collected during the test, and test it again. Their use is motivated by studies of state and federal programs that have repeatedly found that opportunities for educators to tailor programs to meet their local needs and circumstances leads to support for new program initiatives and the local capacity to run them. By iteratively testing PASL in the district schools – by starting with a single classroom and moving onto more classrooms and, later, more schools – the Scale Up Center team was able to limit risks associated with early failure and allow the innovation to be gradually modified, or adapted, to the uniqueness of the system in which it was being implemented.

As improvement science is concerned with building capacity for sustaining ongoing change in organizations, a primary objective of the Scale Up Center project was to leave behind capacity in the districts for future efforts to design, implement and take to scale innovations aimed at solving local problems and improving student outcomes. According to Cohen-Vogel, “it’s not enough to leave behind a ‘proven’ program or practice. Rather, we strive to leave behind what Deming called ‘a system of profound knowledge’ about how to enact change in an organization.” Key to the work is the development of organizational routines that help innovations travel through a system, habits of mind that conceive of teachers and other practitioners as co-creators in the design process, and improvement teams within school districts organized around persistent problems of practice and using data collected in PDSA cycles to solve them.

Learning from ‘dilemmas’

While there is a growing body of research regarding the benefits of improvement tools in education, there’s been little examination of how researchers and practitioners actually work together for improvement. The five years of the Scale Up Center’s work in Florida and Texas offered an opportunity to gain deep insights into how researchers and educators interact in research-practice partnerships, including identifying challenges to be addressed in future improvement work.

Cohen-Vogel and others, in a paper – “Organizing for School Improvement: The Dilemmas of Research-Practice Partnerships” – examined some of the challenges they encountered as they worked together to design, test, and scale a prototype for boosting students’ social-emotional learning. To do so, they gathered data not only on the implementation and efficacy of the prototype, but also on the ways researchers and practitioners worked together and the challenges they faced.

In reviewing nearly 500 hours of recorded conversations, documents, and interviews with partnership members, Cohen-Vogel and her team identified eight challenges faced by the partners in Broward and Fort Worth. As they worked, they realized the challenges represented “dilemmas” to be managed, instead of problems to be solved. Dilemmas present situations with equally valued alternatives. As such, when confronting a dilemma, the challenge is not to choose from among alternatives, but to act intentionally to manage the dilemma. When dilemmas are known and managed, partnership members understand where other partners are “coming from” and sharpen their attention to agreed-upon goals.

The Dilemma of Organizational Goals typically describes the tension between organizational objectives and the motivations of individuals. This dilemma was seen in several ways. In one, differing incentive systems among partners led to conflicting interests between organizational and individual needs. For example, researchers with academic appointments are typically rewarded for published findings around generalized problems of practice they may help fix. While individual school-level reports are needed for a successful PDSA cycle, they may have little scholarly value on their own for researchers.

The Dilemma of Hierarchy describes the tensions around where decisions are made in organizations; such as, top-down versus bottom-up, centralized or decentralized. In the Scale Up Center work, representatives of different levels of the school districts – teachers, principals, central administration officials – were included in the teams. Questions sometimes arose about who owns the decision-making with the improvement work, questions that had to be recognized and negotiated.

The Dilemma of Professionalism describes the tensions around how much decision-making power is allowed for the individual educator. Scale Up Center researchers found this dilemma to be less of an issue, except that some teacher partners were concerned about external pressures they may face in developing and implementing the project’s innovation.

The Dilemma of Task Structures was described by Ogawa et al. as the tensions between formal and informal aspects of the relationships among an organization’s members. Rules, regulations and policies are an example of formal structures. But informal structures, such as common, unwritten understandings among an organization’s members, can either sustain or undermine the formal structures. In the Scale Up Center work, teachers were sometimes suspect of the authority development teams actually had to design and implement a new program. Some also wondered whether there would be administrative backing of the innovation work.

The Dilemma of Organizational Boundaries describes the sometimes unclear distinctions around where an organization’s membership begins and ends. The nature of relationships in improvement work, Cohen-Vogel has found, introduces a dilemma of boundaries that may not arise in traditional research where researchers position themselves as outside observers. Researchers in Broward County reported that after initially feeling that they were being considered as full members of the district community, they subsequently felt themselves being treated as outsiders. In one example, they were discouraged from walking to interviews and focus group sessions without a school staff escort.

The Dilemma of Persistence describes the tendency of organizations to maintain current structures and practices, even when they are attempting to adopt changes. The Scale Up Center researchers found this dilemma frequently. In one example, researchers found that the improvement work often attracted key district and school practitioners who were most vested in buffering against change in their organizational environments. Also, practitioners often expressed concern about adoption of a new curriculum because of the uncertainty it would introduce.

The Dilemma of Compliance describes how individuals and organizations sometimes take symbolic steps to comply with formal requirements. Schools and educators often balance between meeting technical requirements, while adopting symbolic steps to meet community expectations. An example would be seeking to meet the expectations of prohibitions on religious observances but allowing “holiday parties.” In the Scale Up Center work, district administrators often voiced strong support for the innovations, and teachers and staff understood they were expected to participate. But some participants sometimes engaged in behaviors that could be considered symbolic, such as making posters and T shirts touting the innovation being pursued, and pointing to those as being evidence of the school’s involvement while not fully taking part in innovation activities.

The Dilemma of Evidence is an additional dilemma that was uncovered by the Scale Up Center work – one that proved to be fundamental to the efforts. The dilemma centered around differences among partnership members over what counts as evidence an innovation was effective. At times, tensions arose when some data collection behaviors by practitioners challenged sampling norms practiced by researchers. Partners also faced concerns about their own participation and objectivity. Some researchers worried about their own objectivity as they got involved in the conceptualization, design, development and implementation of an innovation. As a result, researchers took part in activities intended to help them navigate the roles they occupied, such as outlining in a memo to other team members the types of activities they considered appropriate for themselves. Additionally, practitioner members of the teams struggled with what counts as evidence. For example, some argued that their own lived experiences should hold more weight in design decisions than those of researchers. Some practitioners also argued that there was not as much need for documentation as researchers expected. Some teachers expressed the feeling that the “paperwork” primarily benefitted “the research” and not the improvement efforts.

By identifying these dilemmas, Cohen-Vogel and her team generated insights into how research-practice partnerships might better organize themselves for future school improvement work.

What’s next?

Research-practice partnerships are a useful mechanism for making educational research more relevant and for making practice more responsive to what is learned from research. In executing improvement science in education, a major undertaking lies in the work of respecting the professional identities, norms, and formal and informal tasks of individuals within organizations, while designing new structures or routines to support the work.

Understanding the dilemmas inherent in research-practice partnerships and in IS efforts in education can help people engaging in this work to forecast challenges – and be better positioned to manage them:

- Understanding and balancing differing organizational goals. Ways must be found to balance researchers’ needs to publish and add new knowledge with the need of district and school practitioners to demonstrate progress toward district goals. One possibility is to ensure that the work of improvement scientists and others involved in engaged scholarship are included in standards for promotion and tenure at universities.

- The dilemma of hierarchy must be addressed in the design of research-practice partnerships. A governing board with power across organizational partners and clear procedures for making decisions is one way to bridge the divide.

- Improvement work can challenge the professional identities of participants, threatening the effort’s goals. Honest conversations – and the trust needed to have them – must be encouraged to help prevent misattributing motives and to facilitate productive collaboration.

- The dilemmas of task structure and organizational boundaries must be confronted. It’s important that the work of research-practice partnerships be supported by formal organizational structures. Boundaries, roles and responsibilities can be established from the beginning, with both researchers and practitioners developing understandings of the constraints under which each other is working. A governing board may be a good venue for renegotiating any roles, responsibilities and tasks.

- The dilemmas of persistence and compliance might be addressed by building on what has been identified as already working in the school. Focusing on ways to improve what teachers and administrators are already doing may increase the likelihood of enacting change. Accountability systems that encourage teachers and other educators to implement improvement tools and techniques can help avoid only symbolic compliance.

Resources

- Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., & Grunow, A. (2010). Getting Ideas Into Action: Building Networked Improvement Communities in Education, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Stanford, CA, retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED517575.pdf

- Cobb, P., Jackson, K., Smith, T., Sorum, M., & Henrick, E. (2013). Design research with educational systems: Investigating and supporting improvements in the quality of mathematics teaching and learning at scale. In B. J. Fishman, W.R. Penuel, A. R. Allen, & B. H. Cheng (Eds.) Design-based implementation research: Theories, methods, and exemplars. National Society for the Study of Education Yearbook. (Vol. 112, pp. 320-349. New York, NY: Teachers College.

- Cohen-Vogel, L., Allen, D., Rutledge, S., Harrison, C., Cannata, M. & Smith, T. (2018). The dilemmas of research-practice partnerships: Implications for leading continuous improvement in education. Journal of Research on Organization in Education. Vol. 2.

- Cohen-Vogel, L., Tichnor-Wagner, A., Allen, D., Harrison, C., Kainz, K., Socol, A. R., Wang, Q. (2015). Implementing educational innovations at scale: Transforming Researchers into continuous improvement scientists. Educational Policy. Vol. 29(1) 257-277.

- Ogawa, R. T., Crowson, R. L., & Goldring, E. B. (1999). Enduring dilemmas of school organization. In J. Murphy & K. Seashore Louis (Eds.), Handbook of research in educational administration (2nd ed., pp. 227-295). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.